Understanding the Origins of the Barbican

The story of the Barbican Complex is a story of architects and other passionate individuals who fought against market forces to reshape the urban fabric in London’s city center. Barbican houses over half the population of the City of London, while the Barbican Centre contains the largest performing arts center in all of Europe. All this very easily could have never existed if it wasn’t for the perseverance of the dedicated Barbican Committee.

The project started as a consequence of the London Blitz leveling sixty-three acres in the City of London during World War Two. While market forces implied this land would be best used with office buildings, a countercurrent was developing at the same time. This counter-economics movement would eventually lead to the construction of the largest residential estate in the City of London and the largest performing arts center in Europe.

The City of London Isn’t London

To clear up any confusion, the City of London is not London. The City of London is the equivalent of New York City’s Downtown, the massively influential historic center of the city and powerful banking business that is slightly over a single square mile in size. The population of the City of London had suffered a long term decline from 100,000 in the 1850s, down to just over 5,300 in 1951, and the area soon to become the Barbican, Cripplegate, had a population of just 28, (source). Today, the Barbican is the most significant residential population in the city, housing 4,247 out of a total population of 9,401.

Fighting For the Barbican

But from the very beginning, the idea of focusing on housing to the land adjacent to the city center was an unpopular fight within the city government. The idea of implementing housing over offices started as a solution to anxieties about the long-term state of the city. Eric Wilkins, Chairman of the Public Health Committee, spoke out as early as 1952, citing the following concerns for building office buildings:having so few residents living near the offices could mean the district would lose its MP; congestion was worsened by the commuters; companies might move their offices closer to the workers; the district could become overly expensive to operate without enough incentives, and eventually the center could be abandoned for alternative business districts. But at this time, the odds of a Barbican being constructed looked bleak. “The Public Health Committee found...that the cost of building flats was high, while controls on overshadowing imposed restrictions on surrounding developments. It agreed in February 1953 to take the matter no further,” (pg. 99).

Following this announcement, wealthy developers started drafting plans to propose an office building in Cripplegate. Direct opposition started quickly, centralizing with the 1953 formation of the New Barbican Committee, with members including those responsible for the Golden Lane Estate, another post-war residential project designed by CP&B for the City of London Corporation.

Origin of the Name

The site’s name reveals the violent conditions that opened up 63 acres for mass redevelopment. Chosen from a street in the war-torn Cripplegate area, a barbican is a projecting watch-tower over the gate of a fortified city. The meaning of this word resonates with the aesthetics of the complex’s massive scale and rough concrete material. This also connects with the area’s history, being on the north border of the ancient Roman wall, and as a post-war development to project London’s strength.

In Defense of the Barbican

By 1956, “...Lord Sandys, Minister of Housing, appealed to the City authorities not to devote this area solely to office buildings but to make ‘a genuine residential neighbourhood, incorporating schools, shops, open spaces, and amenities, even if this means forgoing a more remunerative return on the land,’” (pg 61).

This pushback moved the London County Council (LCC) to consider adding a marginal amount of housing amongst several other office buildings. Powell, a partner at CP&B, wrote that if it wasn’t for his partner Chamberlin, the Barbican could not have existed as it does today, saying that without him, “my guess is that it would have been a very mixed version of the Martin/Mealand plan which the present scheme replaced. Essentially, the Martin/Mealand plan was to cover the site with offices by individual developers, with the optional alternative of a few flats around the church,”

The way how Chamberlin made this argument to the London County Council was to convince them that, “despite the high acquisition and construction costs, it would give the financial return required by the City Corporation if it were built at an exceptionally high density [of 330 people per acre] and if it were aimed at a middle or high-income bracket,” (pg 103).

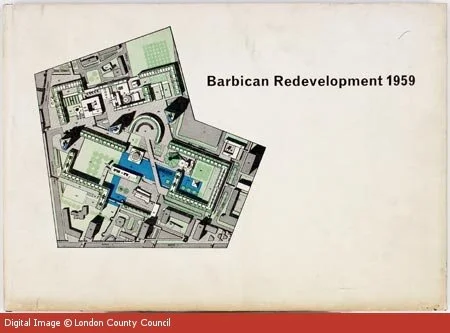

1959 Approval

The architects stuck to their guns, and in 1959, their final draft received approval in principle by the London County Council (LCC). If you’re a perfectionist with an unnecessary flare of eccentricity, I think you’ll like this piece of trivia. After the architects finished their final draft in 1959, “[CP&B]’s researches were collated in a revised design in 1959, produced as an elegant hardback book that the City Corporation had not requested, and for which it paid only grudgingly,” (pg. 111).

The residential accommodations include three 37-story towers, thirteen terrace blocks, and two mews. The height of the towers kept increasing throughout the planning to free up ground space while maintaining a target density. Integrated into the complex are the Barbican Arts Centre, a museum, music school, a girls’ school, and at one point a YMCA.

The Architect’s Intent

“The intention underlying our design is to create a coherent residential precinct in which people can live both conveniently and with pleasure. Despite its high density the layout is spacious; the buildings and the space between them are composed in such a way as to create a clear sense of order without monotony. Uninterrupted by road traffic (which is kept separate from pedestrian circulation through and about the neighbourhood) a quiet precinct will be created in which people will be able to move about freely enjoying constantly changing perspectives of terraces, lawns, trees and flowers seen against the background of the new buildings or reflected in the ornamental lake.”

One other issue Chamberlin fought for should be of particular interest given today's economy. He argued that there was, “a need for more small flats in the City, particularly for young people,” (pg 110). This ties in with the larger ethos of the Barbican, and I think it is notable that such flats do not even develop by chance in the economies of the past, but had to be defended by architects against those focused simply of remuneration.

Post-Approval

Even after this final draft was approved, the soon-formed Barbican Committee was not known for having many friends, and the project continued to face headwinds from within. “Although the Barbican scheme was approved in principle in December 1959, to the architects there always seemed to be more opponents among the City councilors than supporters,” (pg 113). These enemies included the City Architect, Edwin Chandler, who did his best to oppose the project at every stage.

The Barbican Today

The final product by CP&B and the City of London Corporation is a rare example of a 20th Century housing estate that functions in a Western city. This accolade can be attributed to the high investment and a Western prejudice against public housing as a symbol of poverty. Though owned by the City of London Corporation, the apartments were intended for the middle and high-income employees of the nearby city center and apartments remain priced at market rates.

As with most architectural styles that had once been universally despised, the brutalist architectural movement has come back into vogue. Looking towards online communities, one can find people saying of the Barbican, “Fucking love the Barbican. I’ll never be able to afford living there.” Another commenter sharing that, “Barbican flats are amazing too. They get so much light through those giant windows and the layout is incredible.” Of similar value, several people describe the Barbican as, “smooth,” conveying insight both about themselves and the places where I gathered this information, a Facebook community page.

The newfound love for Brutalism is symbolic of a new appreciation for its place in history as a cheap method of providing housing during a period where young people are having an increasingly difficult time finding homes. In this vein, the Barbican reminds us that it will take people fighting against the odds with the government for there to be any significant change in the urban landscape.

Please like and comment down at the bottom of this page.