New Photographs from Toa Payoh, Singapore's First Fully-HDB Built Satellite Town

SINGAPORE—Toa Payoh has an outsized role in the history of Singapore’s urban planning. When construction started in 1964, it was expected to set the course for the future of public housing, which is now how 80% of the citizens are housed. The aesthetics, form, and planning for the area have set the tone for the Singapore heartlands. It followed Queenstown’s lead by becoming the second public housing satellite town, and the first to be planned and built entirely by the Housing & Development Board (HDB).

First Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, knew the future success of the fresh-faced government would depend on the success of the public housing plan, and Toa Payoh [pronunciation] was going to be their first jewel. When reflecting on the legacy, Lee Kuan Yew posited that “Toa Payoh...was planned as a model for other new towns… [it] proved that properly planned and managed urban growth [outside the city] was achievable” (foreword).

For today’s photographs, I focused on a small section of Toa Payoh. I spent a good amount of time hanging around and documenting just a dozen or so blocks outside of Town Centre, ie. blocks 53-62. Most of the blocks I captured were part of the original development, with a few other blocks added late. The design was Corbusian, modernist. The simple lines and imposing width of the buildings make for an all-consuming environment.

Toa Payoh Land History

In Malay, Toa Payoh means “big swamp”. As that implies, the land was not particularly fertile and was difficult to develop. In the 19th century, it had been used for moderate production of pepper and gambier. The villages that started to develop in the area, like Kampung Puay Teng Keng, hosted a close community of mostly Chinese immigrants. The occupants saw this community as loving. The layout was such that moving from your house to your neighbors was easy, and food could be shared often.

The island population had bloomed five-fold to nearly one million between 1900 and the 1950s, and this problem may very well have been felt the hardest in Toa Payoh. From 1947 to the mid-1950s, the population of Toa Payoh doubled to a quarter million, and the people were almost entirely living in attap and wood house kampungs. “When the bulldozers arrived, Toa Payoh consisted of some 10 kampungs” pg 28. An in each kampung, one local estimated there to be around 100 attaps each.

“For the villagers, however, this change incited great fear. Most of them lived off their small plots of land for a living, and this transition would lead to them losing their source of livelihood”(source).

Taking a Stand Against The HDB

The plan to develop Toa Payoh was announced in 1963. The project’s job-creation aspect was marketed heavily in an attempt to persuade the attap dwellers, with a hotly negotiated compensation offer as well. “No actual development of Toa Payoh could be carried out until 1964 because the heavy resistance by some squatters set back the resettlement by some two years” pg 30. It is said that an agreement of $300 compensation for the long move was to that success.

Before that, in the 1960s, the 5-Year Programme was still just an abstract promise by an unproven government. The bulldozer coming for your home? That was real.

One story recounts Lau Ang, a noodle seller, who tried to stop the bulldozers coming for his. Let there be no illusion of success to this story. It was not a flashpoint for Toa Payoh, as this story was cooly relayed by a then-young boy who worked with him. His sentiment was shared among many.

In 1964, Lau Ang wanted to make a stand against this, he wanted to save his home. It is described that he stood in front of the bulldozers, likely begging for the operators to take pity on his home. The police to get him out of the way, and the men carried on. Lau Ang did not care that this had to be done for the future, he just wanted to stay in his home. “It was not so much that he was anxious about the future; he was just deeply sad to lose the only home he had known” (pg 27).

Kampung Conditions Really Were Miserable

The urban layout of kampungs is worth further study. They develop organically, and as an opposite to modern convention, they exist around nature rather than tear it all down. More than that, they cultivate community with neighbors. They also, unfortunately, are a great environment to spread disease and were particularly prone to calamity during natural disasters.

“Life was simple but not easy. Quarrels would often start as a result of the jostling in the queues for water at the standpipes” pg 29.

I think in an ideal Singapore, the suburbs in Bukit Timah and elsewhere could more closely resemble a modernized Kampung plan. They developed in the tropical climate with low-energy costs, high density, and easily solvable problems given modern technology. This, of course, is not to recommend a return to the Kampungs of the old days. The urban form of the kampung is worth reviving, but the exact state of it is most certainly not. To make the ails of the Kampung alive, I will turn to the following statement by Liu Thai Ker, an architect and former master planner of Singapore from an oft-quoted interview with CNA:

One day after the rain, I asked my HDB colleagues to walk with me along Redhill which is now called Redhill Estate. It was a squatter colony and as we were walking on the mud road, rainwater was still flowing down the sloping road. In the water, there was human faeces, pig faeces, rubbish and so on... I should have saved one or two or three hectares of squatter areas, keeping them exactly as they were, including a lack of sanitation, and maybe including a standpipe. Nowadays, when I ask young Singaporeans in their 40s if they know what a standpipe is, nobody knows.

Another issue pronounced in Toa Payoh more than anywhere else in Singapore was a real issue with a lack of oversight and government assistance. This lead to social stratification, crime. Gangs took advantage of the power vacuum, which made the problem significantly worse.

“Before the 1970s, no taxi driver would have dared to enter Toa Payoh after dark...So rampant was the lawlessness that Toa Payoh was called the ‘Chicago of Singapore’ - a moniker that lasted well into the 1970s when a new town was erected there.” I think when reporting on gangs, it’s important to acknowledge the real civic role they played, and the violence they could exact if they were not treated as an authority.

In the Name of Progress

The Housing and Development Board was formed in 1960. In 1959, before the HDB, the Colonial version of public housing, the SIT housed 9% of the island’s 1.5 million people. By 1969, 32% of Singapore’s 2 million people were in public housing. The 106,418 units required to do this were built at an incredible pace, and a third of this was possible thanks to Toa Payoh.

“At the end of its first year of operation, HDB was building its multi-storey flats at a cast that was the lowest in the world” (foreword).

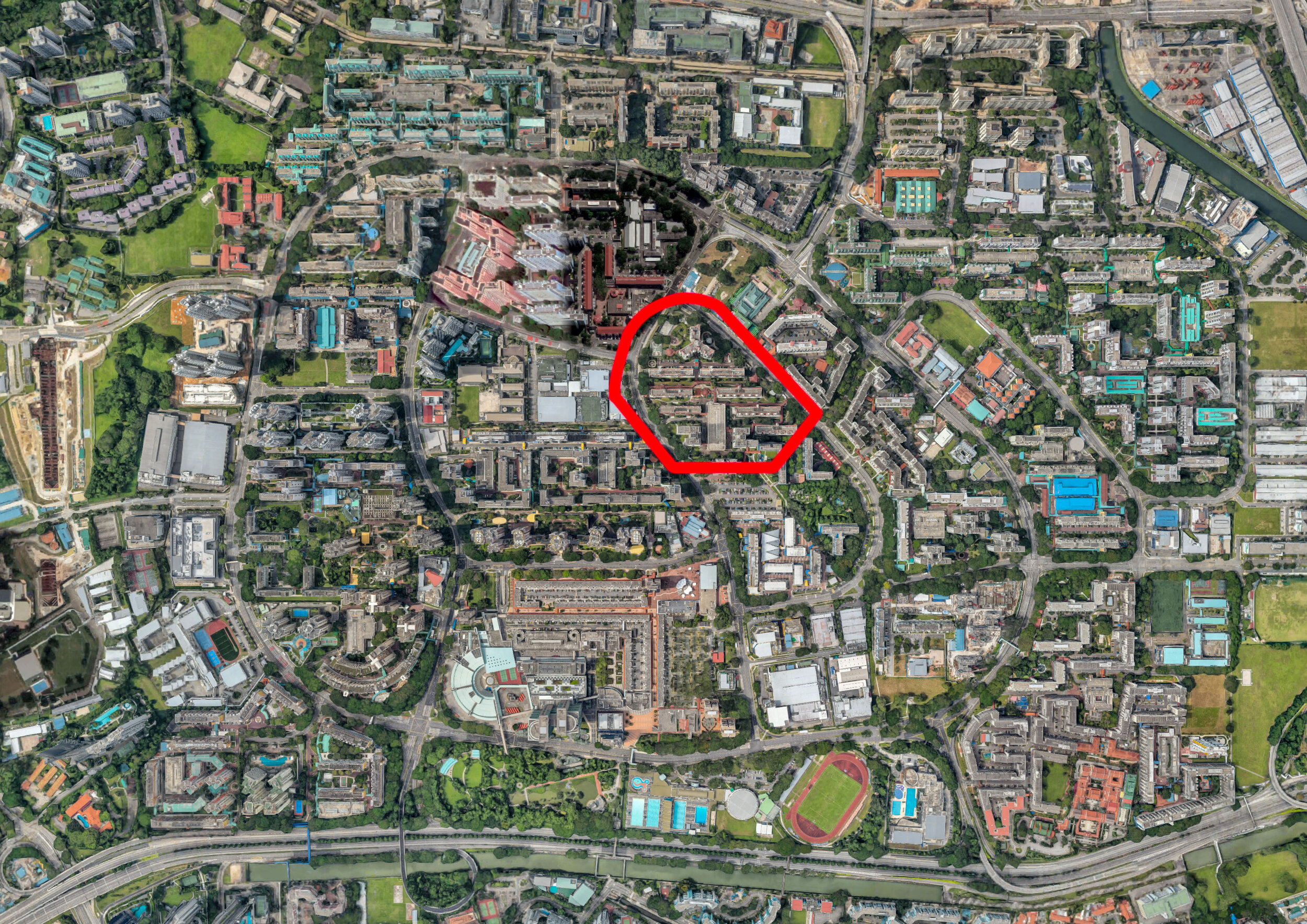

The second Satellite Town is housing over a hundred thousand people. The area is big, and its footprint is distinctive from the air. It is surrounded by an egg-shaped ring, with four-lane roads wiggling inside the ring between the one hundred distinct towers containing 30-35,000 apartments, 55% for rent, 45% to buy. Also included was parking space for 1,000 vehicles (source).

Image of the Queen on top of Block 53

Toa Payoh Aerial View, image from National Archives of Singapore

Close up of the Observation Gallery she visited, obscured by retrofitted roofing

The views she would have enjoyed from the building, as documented from the top floor

Toa Payoh’s Block 53 is a distinct ‘Y’ shaped tower oriented around a circular center, difficult to capture, but I tried my best with the image above. It’s the very tower that Singapore showed to Queen Elizabeth II in 1972 and 2006, as well as an acting Prime Minister of Australia in 1968 and a few other VIP guests to the island. Why this is significant to the history of Toa Payoh is because they have played a crucial role in Singapore’s international urban planning awareness campaign.

The building has received a facelift! I couldn’t determine when this happened, but the four-story pilaster arches have been added to many of the buildings in the area. In a similar vein, the elevator bay entrance or Block 53 now has a pediment protruding several feet out, a good option for providing more covered space around the elevator as a refuge from torrential tropical downpours.

There are questions on this topic I have left which I did not have time or space to answer in this post. The pediments and other similar sheds over the walkways were added after the master plan to address the climatic constraints of the tropical island.

Some Popular Landmarks:

The Dragon Pillar

Along Lorong 3, a weathered statue of a Chinese-style dragon entwining a pillar marks an entrance into Toa Payoh Palm Spring. This is similar to the dragon fountain at Block 85 Whampoa Drive but much smaller and less elaborate.

The Dragon Playground

You just know soon enough I’ll do an entire article about this, but this was my first time visiting Singapore’s most famous playground, and I wanted to share it as soon as I could. It was designed by Mr. Khor Ean Ghee and built in 1979. The distinctive color comes from terrazzo tiles. This was following complaints about fading colors from earlier playgrounds.

It is one of two remaining playgrounds of this design and era. The other is in Ang Mo Kio, but its sand has been replaced with rubber mats.

Other HDB Documented: 62B Lorong 4 Toa Payoh

I don’t have time to do any research at all about this building, but it’s incredibly fascinating! There were two central airways. I hope to return later and document the full of the building and dig into the architect and history of the design. For now, I hope they provoke some thought into experimental design.

62B Lorong 4 Toa Payoh was developed by HDB, as you’d expect, and completed in 2001. It holds a 99-year leasehold.

Conclusion

I want to acknowledge the National Library for their tremendous archives. I spent several hours pouring through a few different books focused entirely on the history of Toa Payoh, and it is what has allowed me to get an interesting and dynamic story for today.